In ‘Yellowstone,’ Transplants to the West Are the Enemy. Is the Hit Show Right?

Posted: October 3, 2022Source: Outside, By

A writer in Bozeman, Montana, grapples with the wealthy wave of newcomers gentrifying the town she moved to ten years ago—as a dirtbag pursuing the western dream.

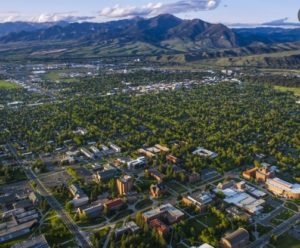

As far as I knew, any notable money in the area was channeled to Big Sky and the ghastly specter of the Yellowstone Club—in the real world, Bozeman was plenty affordable for someone living off coffee shop wages and the occasional dog-sitting gig. The town felt compact but never claustrophobic: Montana State University and local businesses were bordered by expansive pastures that swept into foothills before rising into mountains visible from downtown. Hit TV shows about the region didn’t exist yet, and no one could have predicted that a global pandemic would accelerate the bloated expansion of a town I’d somewhat accidentally landed in.

I felt like a harmless cog in a community of aspirational college graduates looking for accessible climbing, biking, and hiking. What I didn’t think about was how our seemingly modest presence was changing the culture and landscape, transforming Bozeman from a town of ranches, dirt roads, and classic diners to a hot destination with a sprawling REI, multiple sushi restaurants, and nearly a dozen local breweries.

Now, it’s changing again. A new wave of remote workers, wealthy second-home owners, and urban dwellers looking to escape claustrophobic city life during the COVID-19 years have swarmed the valley, snapping up homes above asking price and waiving the inspections.

These days, within five minutes of my house, I can get a CBD smoothie, Botox, and an $18 cocktail. There’s a Lululemon on Main Street, and it seems like every new restaurant name has a vendetta against vowels. McMansions dot the foothills with man-made ponds dug into acres of non-native grasses—a cruel jab to a drought-stricken landscape. Rents for two-bedroom “luxury” apartments in Bozeman now range from $1,400 to $2,400, and the median price for a single-family home is $800,000. Core members of the community have left, because of the cultural changes, or being priced out, or both.

My instinct is to bash this newest generation of transplants—abundantly wealthy and full of media-fueled romanticization of Montana—but my aversion comes with an asterisk. I’m a transplant, too, and no matter how long I’ve been here, I will never be from Montana. How many years do I have to live in a place before I can mourn the cultural shift and the heartbreaking rate of development? Can I answer the question of who deserves to live in the West? Being a resident and watching these changes happen in real time make the answer even less clear.

I’m far from the only one thinking about this. In fact, the most-watched show in the country is about similar tensions playing out in a fictional version of the region surrounding Bozeman. The Paramount Network show Yellowstone takes a preservationist stance on the influx of wealthy, coastal transplants to Montana. In the show, the Duttons, a legacy ranching family, fight to protect their land from soulless developers. Granted, the Duttons’ situation—owning the largest ranch in the U.S. and feeling threatened by a developer wanting pieces of it—is very different from the standard Bozeman resident getting priced out of two bedroom apartments. But the show’s tension is relatable.

Everyone wants a piece of this majestic scenery, and in visually stunning episodes, the Duttons prevail in narrative arcs that wrap up neatly by the end of each season. In this simplified, digestible manner, the show gets it right. If the area was facing a caricature of a developer bulldozing hundreds of acres of the valley, I might feel hopeful that the rapid development could be slowed. But if you side with the Duttons, you have to be ready to answer the question: OK, who does deserves to be here?

The popularity of the show has generated even more interest in southwest Montana, and has helped launch a thousand takes on the area’s spiraling cost of living. Perhaps the most widely talked about was a recent New York Times opinion piece by columnist Ross Douthat, which caused a stir on social media, where Westerners heckled Douthat for trying to diagnose Montana’s woes after watching Yellowstone and taking a brief road trip to the region.

It also didn’t help, in these parts at least, that he tried to make a case for settlement by smitten newcomers. “As an Easterner accustomed to big cities and dense suburbs, to experience the West’s mixture of majesty and emptiness is to feel more intensely what John Dutton’s various foils and rivals feel,” he writes. “That something extraordinary is being effectively hoarded here, with whatever admirable intentions, and that more Americans should be able to live in the shadow of such beauty.” Douthat argues that everyone deserves a piece of western heaven, and that Montantans have no right to hog their wide-open spaces. He doesn’t think a little more population density in such a massive state would necessarily be a bad thing, and that no one truly owns the rights to these places.

While I can’t argue directly with any of those points, I feel strongly that this is the opinion of someone not embedded in the culture and community. While Douthat acknowledges the “coastal gentrification,” and mentions Bozeman as a case against expansion, he understates the insidious, irreversible cultural shift that accompanies rapid population increase. It’s true that long term residents live here for reasons that may entice others: the lack of population density, the open spaces. But if this growth explosion continues, those reasons vanish, and what will we be left with?

Here’s where it’s hard to make an argument on either side. If I refuse to accept change and growth, I’m taking the stance that certain people don’t belong. If I pretend that nothing is wrong with the current development, I’m putting my head in the sand and ignoring the heartbreaking rate of expansion. This whiplash leaves me stranded in the middle of the argument, my head spinning as I witness the unchecked growth of a town that no longer feels familiar. One part of me wants to frantically build blockades to preserve what’s left of the humble mountain-town culture; the other part knows I can’t. I moved here, too, and the newcomers who see what I saw in 2012 also deserve to follow their desires.

If something doesn’t give, I’m left with the question of who this place will be for once all the land has been developed, the ranches have been subdivided, and everyone under a certain income bracket has been priced out. I wonder what will be left of the town we moved to, and where we’ll all end up.