Now and then: Photographs document habitat changes in Western forests

Posted: August 3, 2017Source: Treesource

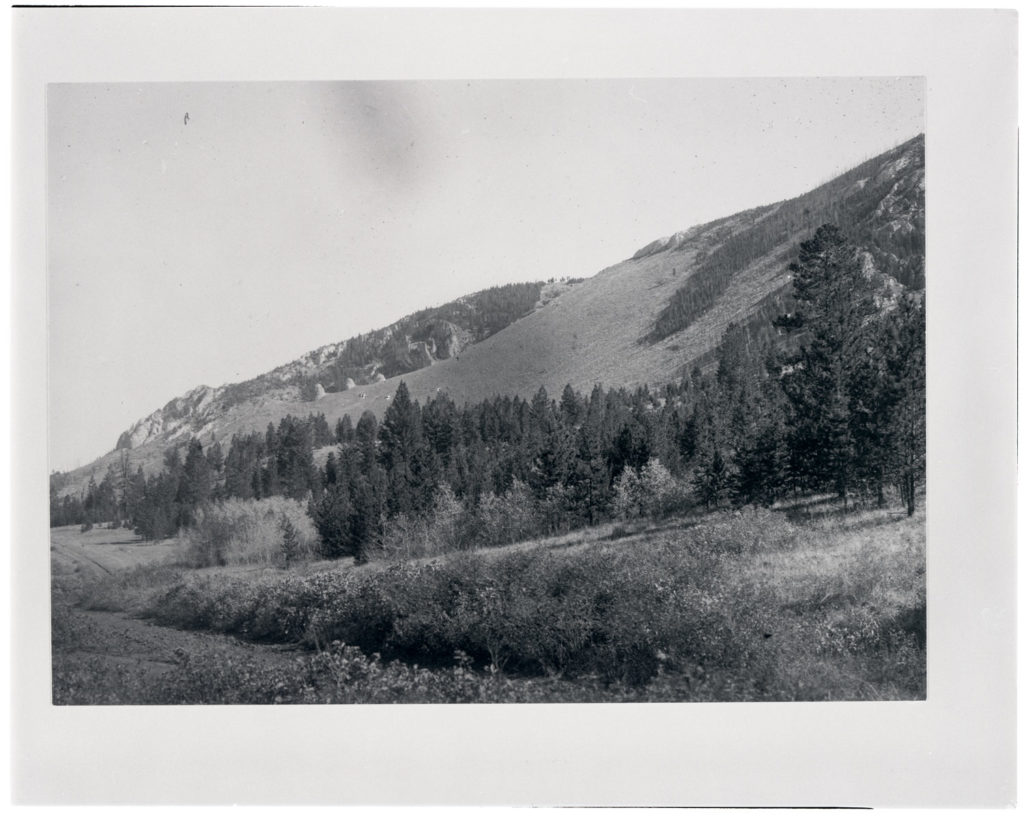

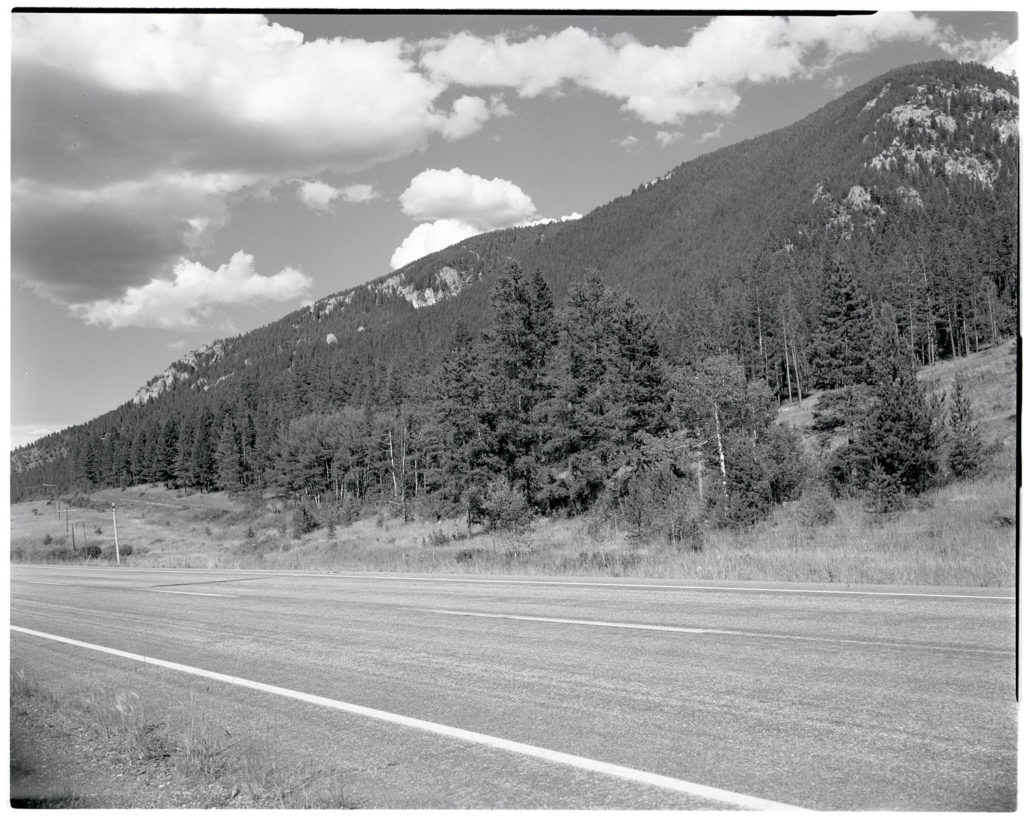

Photo of a hillside northeast of Phillipsburg, Montana next to the future location of U.S. Highway 10A. Date: Between 1906 and 1908 Credit: Frank C. Calkins (USGS) Archived at the Mansfield Library at the University of Montana

In the summer of 1968, the U.S. Forest Service sent wildlife biologist George Gruell into the forests of northwestern Wyoming with a camera, a tripod and an old photograph.

His assignment: Find the exact spot where the photo was taken — and take it again.

Gruell had some old field notes and the vague recollections of a few locals to guide him. That got him fairly close. He walked around holding the photo up to the horizon, comparing it to the scene before him. When he got it just right, he took a photograph of the new scene.

“The bottom line is: It’s a lot of detective work,” said Gruell, who recently turned 90. “You follow up, using your common sense of what you know of the terrain in the area. Many times, though, you’re defeated because of the growth of vegetation.”

A view from the same hillside, now located just off the highway. Date: 07/21/1981 Credit: George Gruell (USFS) Archived at the Mansfield Library at the University of Montana

This technique, called repeat photography, allows scientists and citizens alike to see how a landscape has changed over time. It can instantly communicate a complex message, and has become an effective tool for explaining slow ecological processes, such as climate change or the effects of forest management practices.

Land managers still use this technique to tell stories that are hard to understand with data alone.

Between 1968 and 1993, Gruel re-took photographs of forests in Wyoming, California, Nevada, Idaho and Montana to demonstrate the effects of fire suppression on Western forests. Most revealed thick stands of conifers where there had once been a mosaic of trees, grasslands and shrubs.

Gruell published his photos along with a report interpreting the scenes and the associated management implications. He argued that the elimination of fire had degraded wildlife habitat across the West by reducing the diversity of ecosystems, and recommended prescribed burns as a restoration tool.

“People seem to think that the landscape’s been pretty much the same all through the years,” Gruell said. His photographs showed otherwise.

But in the 1960s, many land managers still saw fire as the enemy, an unwanted force that damaged forests and destroyed economically valuable resources such as timber and watersheds. So for much of the 20th century, the Forest Service considered suppression the only appropriate means of responding to a wildfire.

Still, Gruell continued to present his photos to skeptics in the Forest Service and the National Park Service, making a case for allowing fire on the landscape; increasingly, it worked.

“I talked with numerous people … who had no idea that it had changed like that,” Gruell said. “One person in a pretty high position, he started looking at the landscape around his house and said, ‘Golly, it really has started to change when I look at it.’ ”

As more and more research confirmed the importance of fire in Western forests, federal agencies started to change their approach. In 1972, the Forest Service started allowing some fires to burn in wilderness areas.

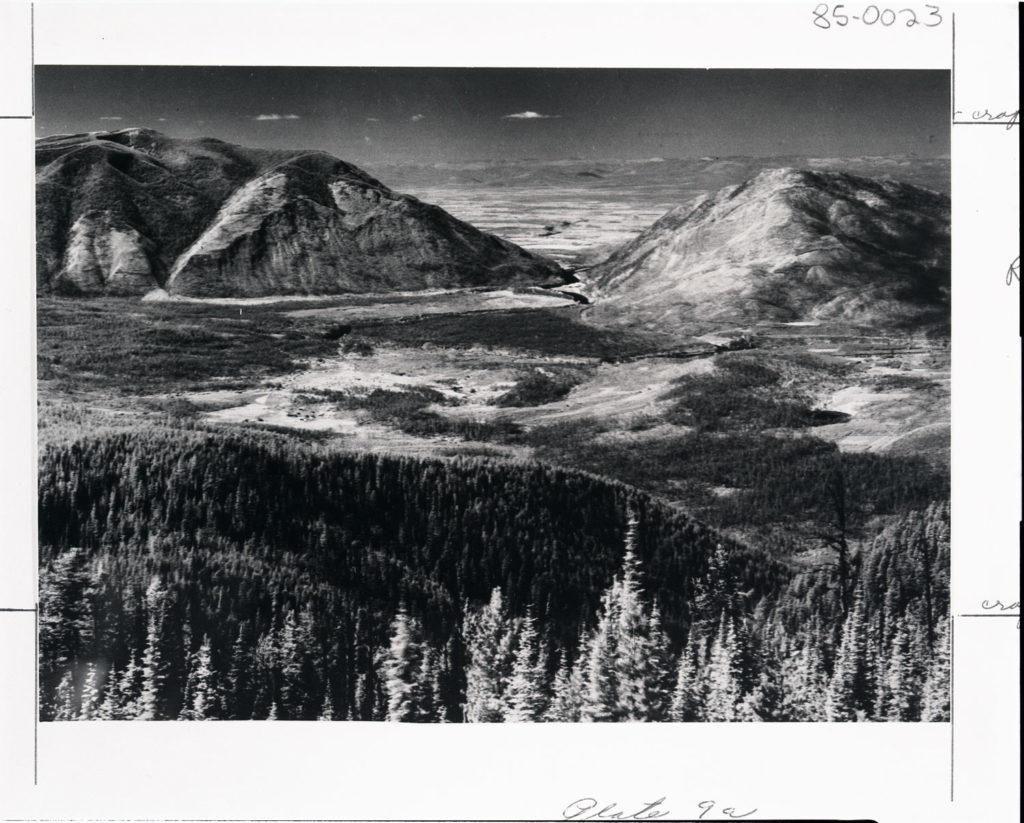

Columbia Mountain and Teakettle Mountain viewed from Desert Mountain in the Flathead National Forest, Montana. An intense wildfire had burned the area six years earlier. Date: 08/24/1935 Credit: E. Bloom (USDI) Archived at the Mansfield Library at the University of Montana

A photo of the same valley more than 40 years later mostly covered in lodgepole pine and Douglas fir. The photo is hazy because of smoke from a nearby wildfire. Date: 08/28/1981 Credit: George Gruell (USFS) Archived at the Mansfield Library at the University of Montana

Last year, the U.S. Forest Service hired Mike Merigliano, a plant ecologist, to re-take some of Gruell’s photos in the Bridger-Teton National Forest.

These scenes will be the third in the series, and they should help land managers monitor the effects of fire management policies, grazing and climate change over time. Merigliano also plans to re-take other historic photos that were not in Gruell’s collection.

“It’s almost like a movie,” Merigliano said. “The more pictures you take, the more you learn.”

Merigliano’s process looks a little different than that used by Gruell.

He has the advantage of new technologies, like Google Earth, to determine the approximate location of the photo and then marks the location with a GPS. Once he gets to the right place, he still has to hold the photo up to the horizon and match it to the scene, just as Gruell did.

Gruell’s and Merigliano’s photographs provide an impressive record of changes in forest cover in the Bridger-Teton National Forest.

Gruell said interpreting the changes in the photos takes some training in ecology and a little common sense. But none of the interpretations are actually based on hard data. The photos offer clues, and scientists like Gruell and Merigliano use decades of research, prior experience and common sense to explain the clues.

According to Andy Norman, a fire specialist at Bridger-Teton National Forest involved in the current repeat photography project, some Forest Service scientists didn’t consider Gruell’s work as ecological research.

But Norman said it may not matter whether repeat photography is true “science.”

“There are some analytical things we can do to look at it,” he said. “But also, it’s just very effective at looking at landscapes and in portraying them for the practitioner.”

Repeat photography’s real strength is communication. Scientists can collect field data or use satellite imagery to answer questions about changes in forest cover, but it’s not always easy to explain their results. Repeat photography offers a way to explain habitat changes to nearly anyone, and Andy Norman hopes these photos will help forecast what might happen to forests in the future.

“The interesting thing now is: What’s going to happen in the next 50 years?” Norman said. “All of a sudden, we’ve increased fire frequency due to climate change. It’s hard to figure out what’s going to happen and what we want as humans.”

Matt Blois is a graduate student in environmental journalism at the University of Montana who writes occasional stories for Treesource.

Crown mountain viewed from across Smith Creek in Lewis and Clark National Forest, Montana. Date: 1900 Credit: Charles D. Walcott (USGS) Archived at the Mansfield Library at the University of Montana

___

Gruell climbed a tree about 50 yards away from the original photo point to take a picture of the same area, now covered by Douglas fir. Date: 09/16/1981 Credit: George Gruell (USFS) Archived at the Mansfield Library at the University of Montana